Self-assessment and Personalized Projects in Math Classes Align Grading with Educational Values

Math teachers generally hope that their students will develop skills in logic, reading, technology, research, and creativity, and grow an appreciation for the many applications of mathematics. However, there are a number of barriers to implementing new teaching methods that emphasize these proficiencies, such as time spent grading, student resistance to change, avoiding student frustration, and preventing the sharing or copying of results. How can assignments and assessments overcome these roadblocks to align with desired learning outcomes or a school’s mission statement?

“Grading should be connected to something we value,” Michelle Ghrist of Gonzaga University—a math professor and director of Gonzaga's Center for Undergraduate Research and Creative Inquiry—said. “Students should gain more than just mathematical knowledge from my classes.” Ghrist detailed her efforts to make this connection in upper-level mathematics classes during a minisymposium presentation at the 2024 SIAM Conference on Applied Mathematics Education, which took place earlier this week concurrently with the 2024 SIAM Annual Meeting in Spokane, Wash. She discussed the development of personalized assignments that offer students independence and opportunities to make their own choices, with fewer ways to cheat and more avenues for authentic individualized assessments.

Ghrist began experimenting with learning-outcome-focused assessments during her 15-year stint at the U.S. Air Force Academy (USAFA). “We really wanted to create a learning orientation culture,” she said, as opposed to a culture that was fixated on grades. This shift could improve student-teacher relationships, cultivate motivation for self-improvement, and intentionally align different aspects of the educational experience. Ghrist was among a loose collaboration of instructors at USAFA who were all iterating on these concepts to achieve clear course objectives, practical descriptions of grades, frank discussions about grades through self-assessments, and meaningful documentations of performance.

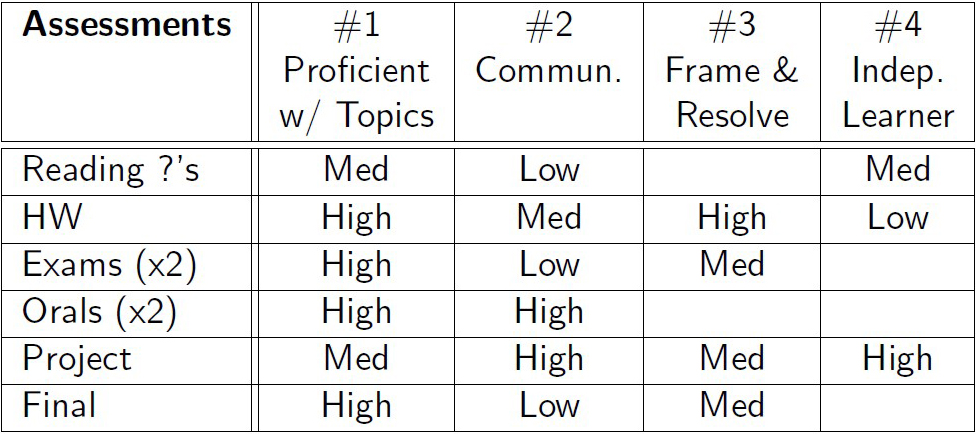

While at USAFA, Ghrist taught an upper-level numerical analysis class that typically enrolled fewer than 30 students, allowing for meaningful one-on-one interactions. Since traditional point-based grading can be a distractor from true improvement and self-evaluation, she instead met with each student individually to decide on their grades together. The goals of these assessments were aligned with the department’s intended outcomes for math majors. Ghrist provided a table in which various assignments—such as homework, exams, and projects—were given High, Medium, or Low levels of particular proficiencies (see Figure 1), which then allowed her to set very specific descriptions of how an A- versus a C-level pupil would perform. Students could then assess their own work based on these clear expectations.

In the latter part of her talk, Ghrist discussed her subsequent efforts along these lines at Gonzaga University. She attended a workshop at Gonzaga’s Center for Teaching and Advising in 2021 that aimed to align individual course assessments with its mission statement, though there was additional relevance to the mission statements of particular colleges or departments. “Then the lightbulb went on!” Ghrist said. “This dovetailed really well with what I had done before. I just needed to make sure to align it with the mission statement.”

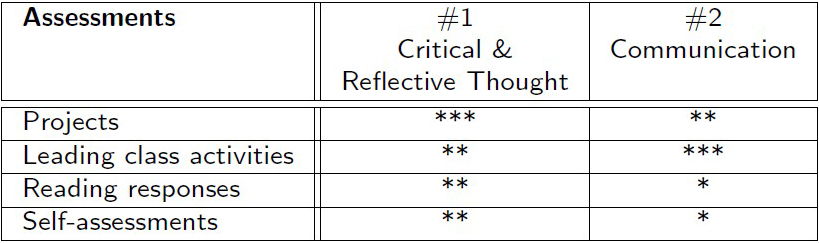

Ghrist adapted her approach to an applied mathematics capstone course as well as an Honors Core Integration Seminar on Quantitative Literacy. The latter had unique challenges, since the course was taken by students from a variety of majors and included a total of nine necessary learning outcomes. “I took all nine of these learning outcomes and lumped them under two umbrellas,” Ghrist said. These umbrella categories were (i) engaging in reflective and critical thought (which was weighted the highest) and (ii) communicating clearly and effectively (see Figure 2). Some course participants provided feedback that they would have liked more grade-based motivation, while others felt that this format actually made them work harder. Other student responses focused on the similarity of the evaluations to those that they may encounter in the workforce, as well as the helpful encouragement for self-reflection.

Lastly, Ghrist delved into some particular examples of personalized coursework. To add individuality to projects, writing assignments, or exam questions, instructors can ask students to explain how and why something occurs, chose the values for parameters themselves, or justify why they set a particular initialization time. To set students up for success with these self-directed problems, Ghrist provides an introduction to technical writing and guides for finding technical resources.

She sometimes assigns students to undertake teaching tasks themselves, such as researching a topic and leading a class about it or producing a two-page handout. In addition, she offers a dynamical-systems-focused project that asks students to choose an article from the references in their textbook or that cites their textbook; they then conduct additional research and write a paper that overviews the article, fills in any gaps, and offers critiques. Ghrist also tasks students with writing mathematical autobiography essays that reflect on their own journeys, in which students discuss what math means to them, how they define math to others, and their own learning styles. In another essay assignment, students write about connections to the future — where they see math in the world, its relevance to social justice, and what role math may play in their lives moving forward.

“I’d like to thank my students for putting up with me trying various things through the years,” Ghrist said. Overall, these projects expose students to real-world applications and help them improve their technical communication skills and synthesize different concepts. While there are certainly challenges—the time investment for grading these projects is significant, for example—students are able to develop important competencies that connect with relevant educational and technical values.

Acknowledgements

Michelle Ghrist’s attendance at the 2024 SIAM Conference on Applied Mathematics Education was sponsored by Gonzaga University's Institute for Informatics and Applied Technology.

About the Author

Jillian Kunze

Associate Editor, SIAM News

Jillian Kunze is the associate editor of SIAM News.

Stay Up-to-Date with Email Alerts

Sign up for our monthly newsletter and emails about other topics of your choosing.